1.3 Practical examples

Here we list some real-world examples where data structures and algorithms are crucial.

Search engines

The World Wide Web (WWW), often referred to as the Internet, has completely changed how we access and use information. With just a few clicks, we can explore an enormous number of websites filled with text, videos, and images on a wide variety of topics. The amount of content available is staggering, with millions of pages and an endless stream of data at our fingertips. But this vast amount of information also presents challenges. It can be overwhelming to sort through all the sources available online. Finding the exact address of a website on your own is nearly impossible.

This is where search engines come in. Search engines like Google, Bing, and DuckDuckGo help us find the information we need by organising the Internet and making it searchable. This process of organising information is called indexing.

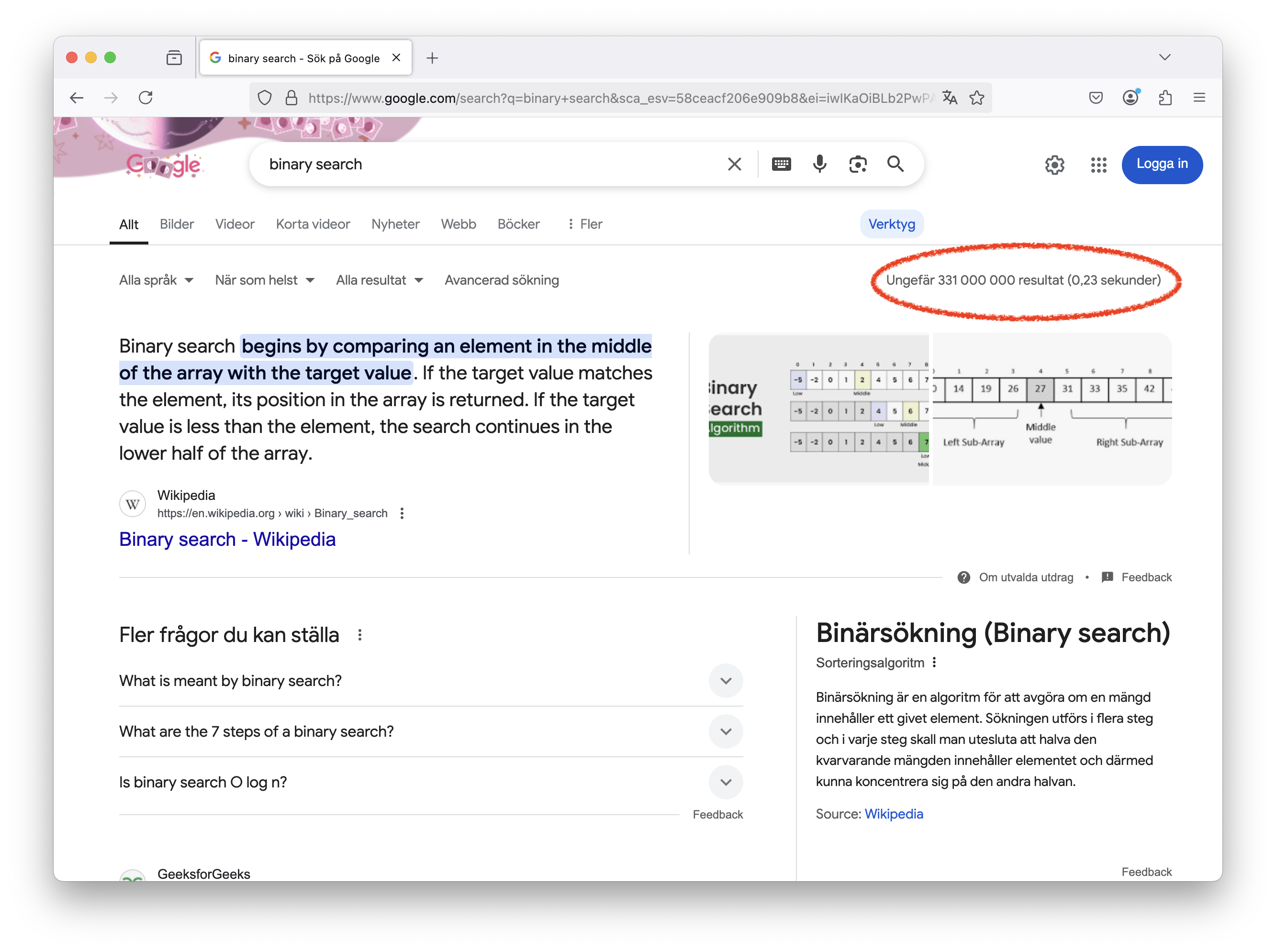

Most of us use search engines every day without thinking about the incredible job they do. The image below shows the results of a search for “binary search”:

It is already impressive to be shown a list of relevant web pages, but it is even more astonishing that, in this case, Google found 331 million results in just 0.23 seconds.

Now imagine you are designing a search engine that must index billions of web pages. Each page has a unique address, called a Uniform Resource Locator (URL), and is associated with a set of keywords. When a user submits a search query, the engine must quickly find all the relevant pages. A simple list is not an efficient way to store and retrieve this information. With billions of pages, it is not practical to check each one in order. Even if looking at a single page takes only a millisecond, going through them all would take years. To handle this challenge, we need smart ways to store and search through the data.

Let’s consider a simpler version of this problem. Suppose we use an array that connects keywords to lists of related web pages. A basic approach would be to go through the array one element at a time until we find the keyword. This works, but it becomes very slow as the array grows larger. To improve efficiency, we can sort the array of keywords alphabetically. Then, instead of scanning from the beginning, we start in the middle of the array and compare the search word with the keyword at that position:

- If they match, we return the corresponding list of web pages.

- If the search word is smaller, we continue the search in the lower half of the array.

- If it’s larger, we search in the upper half.

Each step cuts the number of possibilities in half. So, how many times can we divide the array in half before we narrow it down to one element? This is a logarithmic process, meaning we divide the search space in half again and again. With an array of one billion keywords, we would need only about 39 steps to find the right one.

This model is simplified. In reality, search engines do much more than just match keywords. They also rank pages by relevance and take many details into account, such as whether letters are uppercase or lowercase, and whether the user is combining terms with “and” or “or”.

Databases

A company is developing a database system containing information about cities and towns in Europe. There are many thousands of cities and towns, and the database program should allow users to find information about a particular place by name (another example of an exact-match query). Users should also be able to find all places that match a particular value or range of values for attributes such as location or population size. This is known as a range query.

A reasonable database system must answer queries quickly enough to satisfy the patience of a typical user. For an exact-match query, a fraction of a second is satisfactory. If the database is meant to support range queries that can return many cities that match the query specification, the user might tolerate the entire operation to take a little longer, perhaps a couple of seconds. To meet this requirement, it will be necessary to support operations that process range queries efficiently by processing all cities in the range as a batch, rather than as a series of operations on individual cities.

The hash table suggested in the previous example is inappropriate for implementing our city database, because it cannot perform efficient range queries. The B-tree supports large databases, insertion and deletion of data records, and range queries. However, a simple linear index would be more appropriate if the database is created once, and then never changed, such as an atlas accessed from a website.

Banks

A bank must support many types of transactions with its customers, but we will examine a simple model where customers wish to open accounts, close accounts, and add money or withdraw money from accounts. We can consider this problem at two distinct levels: (1) the requirements for the physical infrastructure and workflow process that the bank uses in its interactions with its customers, and (2) the requirements for the database system that manages the accounts.

The typical customer opens and closes accounts far less often than accessing the account. Customers are willing to spend many minutes during the process of opening or closing the account, but are typically not willing to wait more than a brief time for individual account transactions such as a deposit or withdrawal. These observations can be considered as informal specifications for the time constraints on the problem.

It is common practice for banks to provide two tiers of service. Human tellers or automated teller machines (ATMs) support customer access to account balances and updates such as deposits and withdrawals. Special service representatives are typically provided (during restricted hours) to handle opening and closing accounts. Teller and ATM transactions are expected to take little time. Opening or closing an account can take much longer (perhaps up to an hour from the customer’s perspective).

From a database perspective, we see that ATM transactions do not modify the database significantly. For simplicity, assume that if money is added or removed, this transaction simply changes the value stored in an account record. Adding a new account to the database is allowed to take several minutes. Deleting an account need have no time constraint, because from the customer’s point of view all that matters is that all the money be returned (equivalent to a withdrawal). From the bank’s point of view, the account record might be removed from the database system after business hours, or at the end of the monthly account cycle.

When considering the choice of data structure to use in the database system that manages customer accounts, we see that a data structure that has little concern for the cost of deletion, but is highly efficient for search and moderately efficient for insertion, should meet the resource constraints imposed by this problem. Records are accessible by unique account number (sometimes called an exact-match query). One data structure that meets these requirements is the hash table. Hash tables allow for extremely fast exact-match search. A record can be modified quickly when the modification does not affect its space requirements. Hash tables also support efficient insertion of new records. While deletions can also be supported efficiently, too many deletions lead to some degradation in performance for the remaining operations. However, the hash table can be reorganised periodically to restore the system to peak efficiency. Such reorganisation can occur offline so as not to affect ATM transactions.